The History of the Passion

The Passion of Jesus Christ lies at the very centre of the Christian faith and has inspired a great number of musical works dating from the earliest years of Christianity until the present day. In the bible, the various descriptions of the final episode in Christ’s mortal life on Earth are found in the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, which constitute the fundamental part of the New Testament. Unlike the Gospel of Mark, which was written for the benefit of non-Jews who had converted to Christianity, the Gospel of Matthew was written for the benefit of existing Jews who had converted to Christianity. There are 508 verses in Mark which are also found in the Gospel of Matthew, and it is thought that the Gospel of Mark served as a basis for that of Matthew. Similarly, 230 verses of Matthew’s Gospel are also common to Luke. There are, of course many differences. Matthew didn’t bother translating Hebrew expressions in his writing, or explaining Jewish feasts, as he knew his readers would be perfectly familiar with them. In his writing Matthew, himself a Jew converted to Christianity, assures his readers that Jesus of Nazareth is the long-awaited Messiah and describes, in detail, the environment in which Jesus lived. By the Middle Ages, the word Passion, derived from the Latin passio, had become synonymous with the sufferings of Christ. Passio itself derives from the Latin verb pati meaning “to suffer”. Like the other three gospels, Matthew recounts the whole process of the crucifixion from the conspiracy hatched against Jesus to the entombment.

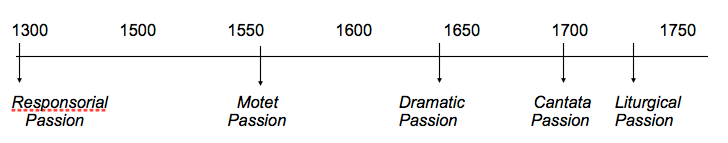

From the Middle Ages it was common practice to intone the words of the Passion story on Passion Sunday (the Sunday before Palm Sunday) and again on Good Friday in a plainsong chant known as a choraliter. The Lutheran church quickly adopted this Catholic tradition and, as the art of composition developed, this soon developed into a polyphonic form which was to pass through a number of stages.

Responsorial Passion |

Biblical text intoned to Gregorian chant as an act of worship. |

Motet Passion |

The entire evangelical text is set polyphonically (e.g. the Passion by Roland de Lassus). |

Dramatic Passion |

The recitative does not follow the biblical text, but is a free invention inspired by it (e.g. the Passion by Heinrich Schütz). |

Cantata Passion |

The performance is separated from a liturgical act of worship and performed in the context of an oratorio. Words are not biblical but written as a libretto (e.g. the Passion by Reinhard Keiser). |

Liturgical Passion |

Performed as a liturgical celebration in two parts, either side of a lengthy sermon, the biblical text restored, but interspersed with reflective arias and chorales for the congregation to sing. This is the structure used by Bach. |

By the time Bach arrived in Leipzig it was customary for there to be a performance of the St Matthew Passion on Palm Sunday and of the St John Passion on Good Friday – both in St Nicholas’s, the Passion being a prominent feature of Protestant religious observance. Bach began the tradition of an annual Passion on Good Friday alternating between St Thomas’s and St Nicholas’s. In Italy the famous opera librettist and playwright Pietro Metastasio had started to compose texts for musical settings of the Passion.

Notes by Peter Parfitt ©2012 Aberdeen Bach Choir

⇐ Bach in Leipzig The Music ⇒