Also from England are early sixteenth-century polyphonic settings such as tonight’s setting by Byrd, and similar settings by John Taverner (1495-1545), Christopher Tye (c1505-1573) and John Sheppard (1515-1558). Prominent settings from continental Europe exist by Lassus (1532-1594), Jacob Händl (1550-1591) and Palestrina (1524-1595). At this time the Te Deum, like the Magnificat, was often performed with plainsong verses alternating with verses of choral polyphony. There are also records of instrumental accompaniment being used on feast days and other significant occasions. A new tradition of Baroque choral settings, with instrumental accompaniment, emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, such as tonight’s setting by Purcell, along with others by Charpentier (1634-1704), Lully (1632-1687), Michael Haydn (1737-1806) who wrote six, and Joseph Haydn (1732-1809). Through the nineteenth century European composers made larger scale settings of the text, written for the concert hall rather than for liturgical use. These included Bruckner (1824-1896), Dvorak (1841-1904), Verdi (1813-1901) and Berlioz (1803-1869), whose Te Deum was written for the Great Exhibition in Paris in 1855. After the Reformation, settings of the Te Deum regularly occupied a place in the Anglican church as the text was included by Thomas Cranmer in his Book of Common Prayer of 1549. There is a modified and modernised version of the plainsong included in the musical setting of the liturgy by John Merbecke (1510-1585) which was popular in parish churches for many years, and is still in use today in some churches. Martin Luther’s version was also based heavily on the original plainsong melody and gave rise to settings built on this by Michael Praetorius (1571-1621), Scheidt (1587-1654), Buxtehude (1637-1707) and J.S. Bach (1685-1750) whose setting survives only in a chorale-based form, heavily edited by his son, C.P.E. Bach (1747-1788). The tradition of British festival settings began with a setting by Henry Purcell (1659-1695) written for St Cecilia’s Day (Nov 22nd) 1694. This was followed by Handel (1685-1759) written to commemorate the victory of George II at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743, Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) written to celebrate the recovery of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII of the United Kingdom) from typhoid fever in 1872, Hubert Parry (1848-1918) written for the Three Choirs Festival in Hereford in 1900, and tonight’s settings by Vaughan Williams and William Walton.

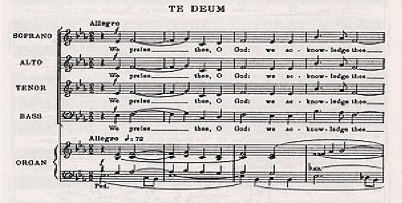

The opening of the Te Deum Collegium Regale by Herbert Howells.

The Composers and the Music

The performances this evening are being given in chronological order of composition; it is possible to see how the music has evolved over the last four centuries

Thomas Tallis (c1505-1585)

Thomas Tallis was probably born in Kent, where he later formed numerous connections and held various appointments. His first recorded appointment was in 1532, as organist of a Benedictine priory in Dover. The next reliable source of his activities does not appear until 1537 where he turns up on the payroll of St-Mary-on-the-Hill in Billingsgate, London, where he was probably organist and choirmaster. In 1540 he went to be organist of Waltham Abbey, but within a year, following the dissolution of the monasteries, found employment as a Lay-Clerk in the choir of Canterbury Cathedral. In 1545 he moved to be a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal1.

1The Chapel Royal dates from 1135 and is still in existence today. It was the single most influential institution in fostering the development of English music in the middle ages and through the calamitous Tudor period and the Reformation. It is not a building, but a body of clergymen and musicians (composers, singers, organists, instrumentalists) responsible for shaping, defining, dictating and delivering the musical and liturgical practices of the day. During the reign of Edward IV (1461-1483) the Chapel Royal consisted of 26 chaplains and clerkes in holy orders, 13 minstrels, 8 choirboys and their master, and a night watchman to keep the hours through the night. By the time of Henry VIII the salaried staff of the Chapel Royal had risen to about 80 individuals, and by the succession of Elizabeth I, there were 114 on the payroll. All of the major English composers received their basic musical education through the Chapel Royal, usually as boy choristers, and in the sixteenth-century the contribution of composers such as Tallis, Tomkins, Byrd, John Bull, Gibbons, Morley and Tye brought the standard of music to one which exceeded the Vatican’s equivalent at the Sistine Chapel. The Chapel Royal produced all of the music and liturgy for royal worship, state occasions, and the reception of visiting heads of state. The Chapel Royal was based at the chapels of St James’ Palace and Hampton Court. Today they operate from those two places and also Buckingham Palace and consist of a much smaller body of boy choristers and adult male singers, and an organist and choirmaster. They are not to be confused with the choir and clergy of St George’s Chapel Windsor, or the Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster (which we know today as Westminster Abbey), which both had (and still have) separate and independent musical foundations.