Henry Willis and the Organ of St Machar's

The current organ in St Machar’s Cathedral was built by the Henry Willis Company of London. Willis (a direct contemporary of the mighty French organ builder, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll) is known as ‘Father Willis’, partly because of his huge contribution to the art and science of organ building, and partly to distinguish him from future generations of Willis organ builders. He was the leading organ builder of the Victorian period (the ‘Rolls Royce of organ builders’) and contributed a fine, four-manual organ to the Great Exhibition of 1851. This instrument won a gold medal and, after the exhibition, was moved from the Crystal Palace and installed in Winchester Cathedral, where it is still in daily use. Other prominent ‘Romantic’ Willis organs from this period which are still in regular use are to be found in St Paul’s Cathedral, as well as the cathedrals of Gloucester, Lincoln, Salisbury, Durham, Canterbury, Glasgow, Edinburgh (St Mary’s Episcopal), Liverpool, Westminster, Hereford and Truro. During the Industrial Revolution, a time when both civic and religious commitment led to the erection of a number of impressive buildings, many towns equipped themselves with imposing town halls, often installing an ostentatious Willis organ as a centre piece. The largest organ in the world at the time, with 111 stops (ranks), was the Willis organ installed in the Royal Albert Hall in 1871. It too is still in regular use. Other prominent locations of Willis organs are Blenheim Palace, the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford and the RAM. An historic and beautiful one in Windsor Castle was destroyed in the fire of 1992. There are many examples of Willis’ work here in the north east of Scotland. Pre-eminently at The Music Hall, but also at Queen’s Cross, and Rubislaw Churches. Although all these instruments have undergone changes over the years, the Chapel at Haddo House houses a fine 3-manual instrument that we are almost certain has never been altered and is as ‘Father’ Willis left it.

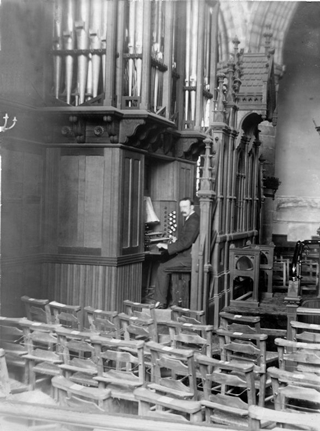

The photograph shows the newly installed organ in St Machar, in its original position, behind the communion table and in front of the East Window.

Roger Williams suggests that the presence of the organist George Dawson in this photo, along with the possibility that there is no third manual yet, suggests that this photo can be dated to sometime between 1893 and 1898.

The following passage, written by Dr Roger Williams is taken, with permission, from St Machar’s Cathedral website.

Nothing definite is known about organs in St. Machar’s Cathedral before the Reformation despite the reference by Leslie MacFarlane to two organ books in the 1436 Inventory. However, in an account of Bishop Gavin Dunbar’s arrival at St. Machar’s in 1519, Hector Boece relates ‘whenever he [Dunbar] entered the church he was greeted by the sweet harmony of voice and organ.’ The Cathedral would therefore appear to have had an organ of some kind or other. Considering Bishop Elphinstone’s arrangements for the music of ‘twenty Vicars Choral, two Deacons, two Subdeacons, two Acolytes and twelve Singing Boys’ (decree of 7th May 1506), it seems inconceivable that there would not also have been an organ of similar generous provision.

In recent years there has been a rethink of what type of organ this might have been. The use of the organ in alternatim (alternating) with the singers would have been one of its main functions. Recalling that Bishop Elphinstone had lived both in Paris and in Louvain, and considering the well-established medieval Blockwerk tradition in continental organ building (producing a very loud), it seems highly probable that there would have been a magnificence about the organ in St. Machar’s. Ideas about the organ having been a small, portative instrument, which had currency some years ago, are now seen as rather unlikely. However, as there is no surviving evidence in the building, we can only surmise by reference to other contemporary sources. These include the Chapel of Elphinstone’s University, just down the High Street. In King’s Chapel there seems to have been an organ which warranted its own gallery, situated on the south side of the building. This is likely to have been an instrument of considerable size and power.

At the Reformation all use of the organ in worship ceased and it was not until as late as 1863 that, after much controversy, organs were once again allowed a place in the Church of Scotland service. Acceptance was initially slow, and St Machar's was quite in the vanguard when the acquisition of an organ was first discussed in 1880 as part of an ambitious restoration scheme for the building. This scheme did not come about, but finally, in 1889, an Organ Committee was established and fund-raising began. At the Committee's very first meeting it was proposed to approach the renowned firm of Henry Willis & Sons, London, 'acknowledged to be the leading organ builders in the kingdom', whose instruments grace the majority of Britain's cathedrals and a great many of its churches and concert halls. A quotation was also requested from the well-respected Hull firm of Forster & Andrews, but it was with 'Father Willis' that the order for the organ was placed in June 1890. Much discussion was still taking place as to its siting. Delay resulted when a favoured location at the end of the North aisle proved impracticable, but in late August 1891 the organ arrived and was set up in a rather dominant position in front of the present East window's large Victorian predecessor. The instrument was inaugurated on 25th September 1891 and was immediately recognised as being of outstanding quality.